Leadership Practices for the Era of COVID-19

Managing Enduring Dilemmas[1]

As the dangers of the coronavirus pandemic were becoming apparent in March 2020, a senior rabbi in California wrote to his congregation:

In our response to this global health crisis, we are attempting to balance multiple, sometimes competing values. Coming to synagogue for study, worship, acts of loving kindness, and for the gift of community itself is fundamental to Jewish life. We now find ourselves in a moment where this impulse can be at odds with the core Jewish value of pikuach nefesh—protecting the health and safety of ourselves and others, particularly those who are most vulnerable to contagious diseases like COVID-19. (Yoshi Zweiback, March 10, 2020)

The rabbi goes on to explain the steps the congregation would be taking at that moment in time, more than a week before city and state officials mandated “safer at home” and “shelter in place” policies, including postponing some events and continuing others online. As time went on and public policies were implemented, all of the temple’s activities, including classes in its large schools, were moved online.

What was this rabbi and this temple’s leadership doing? How were they making decisions? They acknowledged that they were facing a situation in which dearly held values were in tension with each other. At that moment the value of the community gathering for Torah, Avodah (prayer and observance) and Gemilut Chasadim (acts of lovingkindness) stood in tension with the value of piku’ach nefesh (preservation of human life). The situation did not present itself as a problem that could be solved once and for all; the best the leadership could do was manage the dilemma of competing values by deciding that, for the moment, they would take a course of action to close down the temple’s campus.

Responding to crises has always been an integral responsibility of leadership. Leaders often approach crises as a series of problems to be solved and see the effectiveness of their leadership reflected in the degree to which they are effective problem-solvers. In this paper, we present a different view of leadership, leadership as managing enduring dilemmas, and share advice given by Jewish educational leaders who use this practice.

The era of COVID-19 puts this view of leadership in sharp focus. The situations leaders are called on to address are taking place in an environment in which new conditions emerge daily. What looks like a good solution to a problem today may not look so good tomorrow. The current situation calls on leaders of Jewish institutions (synagogues, schools, camps and communal agencies) to abandon the problem-solving mindset and replace it with a stance in which they see their leadership task as managing dilemmas. We call the dilemmas leaders face “enduring dilemmas” because the value tensions at the heart of these situations persist even after the leader has taken action on a particular issue related to these values at a given moment in time.

For the past decade we have been teaching managing enduring dilemmas as a sophisticated and effective leadership practice for Jewish educators. We then studied the professional practice of the educators who learned and gained experience managing dilemmas to see the effect on their leadership over time. In this paper, we connect this leadership practice to Jewish tradition as an authentic reflection of Jewish thought and action and explore how this approach is reflected in contemporary literature on leadership. We give examples of the power of this leadership approach for rabbis, Jewish educators and Jewish professional leaders in three domains in the era of COVID-19: institutional leadership, educational and programmatic leadership, and personal leadership.

Enduring Dilemmas in Jewish Tradition and Contemporary Literature on Leadership

Jewish tradition is replete with examples of values in tension. In a quintessential example, the rabbis debate which is greater, the value of study or the value of action.

Rabbi Tarfon and the Elders were once reclining in the upper story of Nithza’s house, in Lod, when this question was posed to them: Which is greater, study or action? Rabbi Tarfon answered, saying: Action is greater. Rabbi Akiva answered, saying: Study is greater. All the rest agreed with Akiva that study is greater than action because it leads to action. (Kiddushin 40b)

While the conclusion here seems to be that study is more important, the rationale for that value preference is that study leads to action, which is to say that action is also a high value to the rabbis. Indeed, Tarfon and Akiba are among the five rabbis that the Haggadah recounts as staying up all night in B’nai Brak, the center of the rebellion against the Roman empire. Although the text does not explicitly state that they were planning rebellion, they did not stop their conversation until one of their students warned them that the time for the morning prayers had arrived and it was time to stop planning lest they be caught by the Romans. These were men of action! Depending on the situation, they would favor action over study or study over action. They would manage the dilemma of competing values in different ways under different circumstances.

Contemporary social science literature often describes leadership as a process of facing situations with no clear solutions. Hill and Lineback (2019), for example, see management, which to them encompasses leadership, as difficult because of its “inherent paradoxes,” many of which result from value tensions. They say that working with groups and teams challenges managers to value both diversity (to ensure multiple voices) and cohesiveness (to ensure work towards common goals). Their conclusion about “paradoxes,” a subset of which we call “enduring dilemmas,” is that they are never fully and truly resolved and because of them, the “right” management action will always be a matter of judgment. (pp. 20-21)

Rushworth Kidder, in his book, How Good People Make Tough Choices: Resolving the Dilemmas of Ethical Living (2009), refers to such paradoxes as “right versus right” dilemmas in which a person must decide how to act when facing a choice in which both possible actions enact cherished values and yet the person must choose a way to act[2]. Following Kidder, we believe that the key to sophisticated leadership, especially in the era of COVID-19, is to hold values in tension rather than search for a single response that would seemingly solve the problem of the moment.

“...the key to sophisticated leadership, especially in the era of COVID-19, is to hold values in tension rather than search for a single response that would seemingly solve the problem of the moment.”

Managing Dilemmas in Jewish Educational Leadership

Through extensive interviews and document analysis, our study of Jewish educational leaders revealed how valuable these leaders find the practice of managing enduring dilemmas. They recognize that many situations present them with enduring dilemmas to be managed, not problems to be solved. This frees them from the pressure of thinking and feeling that they have to provide immediate and long-lasting solutions to every problem their institutions and the people in them present.

“It is not enough to use one’s intellect alone; leaders must also draw on their emotions in figuring out how to respond to enduring dilemmas. ”

These educators identify several defining characteristics of enduring dilemmas. Most notably, enduring dilemmas appear in the form of two values in tension, both of which the educators embrace and neither of which do they want to give up. Second, any response to an enduring dilemma is “only for now”; it is not a solution that makes the problem go away but is an action that responds to the value tension in light of current circumstances. Third, responding to enduring dilemmas requires deep thinking and deep feeling. It is not enough to use one’s intellect alone; leaders must also draw on their emotions in figuring out how to respond to enduring dilemmas. Fourth, it is often best to engage others in the process of deciding how to respond; the different perspectives people bring enrich the deliberation and lead to more effective actions. And finally, managing an enduring dilemma is not a matter of finding a balance between the two values that are in tension; rather, it is finding a course of action that may favor one over the other for now or may be a creative “third way” that does not directly enact only one of the values. (See Figure 1: Defining Features of Enduring Dilemmas)

Figure 1: Defining Features of Enduring Dilemmas

Thinking about leadership as managing dilemmas rather than solving problems empowers educators to step up and take on new leadership roles with their constituencies. When they face seemingly intractable situations, they find it helpful to ask, “What values are in tension here?” rather than jumping to react. They also realize that thinking this way gives them permission to acknowledge they do not have to fix every problem that they face, and the actions they take at any given moment can be a response for that moment and not forever.

While we completed this study before the COVID-19 pandemic struck, the lessons for leadership could not be more powerful for these complex times. The situations which institutional and educational leaders now face are fluid, changing day by day. People with leadership responsibilities often find themselves facing competing values, and do not want to give up on either one even though in the moment they may have to sublimate one or the other. Perhaps most important, we learned from the educational leaders who see their role as managing an endless stream of enduring dilemmas that the decisions leaders make for right now may be the best they can do under current circumstances. They can continue to consider the values, manage the dilemmas and take different actions as the situations they face unfold. They find this way of thinking and acting to be a tremendous relief.

Enduring Dilemmas in Practice

We have identified three domains of leadership in which enduring dilemmas play out: institutional leadership, educational and programmatic leadership, and personal leadership. The three domains are nested within concentric circles. (See Figure 2: Domains of Leadership) At the core of leadership is personal leadership surrounded by the domain of educational and programmatic leadership which, in turn, radiates out to institutional leadership. How leaders in the Jewish community traverse these circles will change depending where a particular dilemma first emerges but, in many cases, dilemmas manifest in all three domains.

Figure 2: Domains of Leadership

Institutional leadership often involves raising up the two values of masoret (continuity) and hiddush (change).When should an institution push to create change as a way to make Judaism relevant and meaningful to draw in younger members and prevent stagnation, and when should it preserve beloved traditions in order to maintain a distinct institutional identity, often developed over decades and dear to long-time members? In recent years, with the bewildering pace of change, not the least of which is the advent of virtual everything, institutions have scrambled to keep up, to stay relevant to the changing ways in which human connection occurs. The pressure to change has challenged the ability and, for some, the desire to uphold the value of continuity, preserving the past. Ironically, in the world of COVID-19, many now long for the past, yearn to go back to the old ways of sitting together at Kabbalat Shabbat or even coming together for committee meetings and schmoozing in the parking lot. At this moment, when everyone is forced to robustly embrace the value of change which affects almost all the ways Jewish institutions function, many long to be able to embrace the past, the value of continuity and familiarity.

One of the first enduring dilemmas to confront educational and programmatic leaders during the early months of COVID-19 was that of chinuch (education) and keiruv (engagement). Articles appeared in the Jewish blogosphere and in social media groups asking the question, “How do we keep learners and families engaged and socially connected, on the one hand, and how do we continue to provide content of some sort so learners do not fall behind in, for example, their Hebrew learning or Bar/Bat Mitzvah preparation?” Educational leaders seek to educate—to share and enable learners to delve into Jewish texts, holidays, history, and language to enrich their lives and nurture their spirits. Programmatic leaders seek to engage—to provide moments and experiences for Jews of all ages to connect with one another and with community. Context has a direct bearing on how educational and programmatic leaders manage this dilemma. A Jewish day school with its mandate to provide full-time education to its students with a hefty price tag, may start out by providing content to keep their students focused on curriculum and may quickly realize that they also need to attend to students’ sense of isolation and need to provide moments of connection and socio-emotional learning. A congregational youth group may privilege connection and relationships over learning and yet over time may decide to enrich the experience of connection by including Jewish content as part of the connection experiences they are offering. Both values, education and engagement, are related to the values of the institution at large.

Professional leaders in the Jewish community also face enduring dilemmas of a deeply personal nature, dilemmas that in turn challenge them professionally and have ramifications for their institutions. The value tension of kavod(respect) and achrayut (responsibility) is just such a dilemma. In their study Decent People, Decent Companies: How to Lead with Character at Work and in Life (2005), Turknett and Turknett refer to this value tension as the leadership character model. Respect, they say, is the combination of empathy, lack of blaming others, emotional mastery, and humility. The application of these characteristics moves leaders to care for the people with whom they work. Responsibility is the combination of self-confidence, accountability, focus on the big picture, and courage. The application of these characteristics moves leaders to fulfill their responsibilities to the organization. Moving back and forth, applying different characteristics to different situations, is the most effective way to manage this enduring dilemma. The realities of COVID-19 and the resulting economic crisis have called on institutional leaders and educational and programmatic leaders to move deftly, sometimes privileging kavod (respect: caring for others) and sometimes privileging achrayut (responsibility: getting the job done). Turknett and Turknett believe that managing this dilemma successfully lies at the core of personal integrity. Leaders with integrity never lose sight of their respect for people or their responsibilities to the organization even though at a given moment they may be subordinating one to the other. What is at stake in managing this dilemma is not only the people and the organization, it is the leader’s sense of self, their core, their integrity.

Starting Out to Manage Dilemmas – Advice from Professionals

In the time of COVID-19 traditional boundaries between the professional and the personal, workplace and home, have become more permeable and blurred than ever before. A similar permeability comes into play when managing enduring dilemmas. Enduring dilemmas are values-based, often involving values that are dearly held both professionally and personally. Therefore, it is not surprising that the advice from leaders in the field who engage in this practice centers around a dialectic in which they move from their personal selves to their professional selves and back again as they manage the value tensions they are facing.

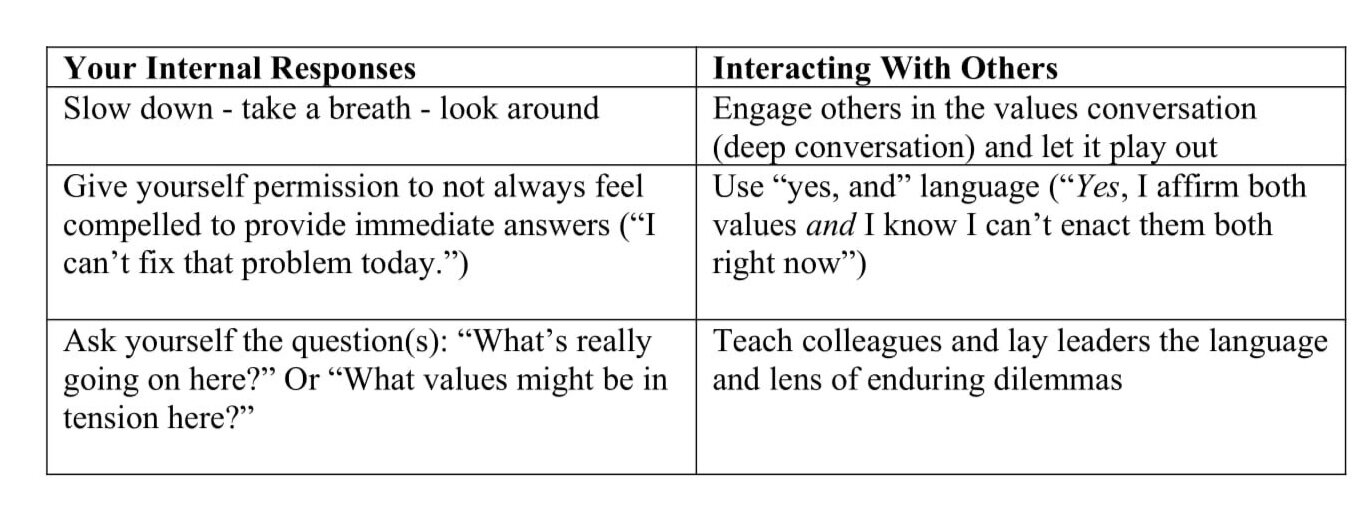

Jewish educational leaders who have adopted the practice of managing dilemmas provide advice about internal reflection and processing as well as external interactions and processing with others. Beginning with the internal, they suggest that when leaders face what seems like a problem but might indeed be a dilemma they should slow down, take a breath and notice their emotional response to what is in front of them. They then ask, “What’s really going on here?” or “What values might be in tension in this situation?” and give themselves permission not to feel compelled to provide immediate answers. As one leader noted, “I learned to say, ‘I can’t fix that problem today.’”

“...when leaders face what seems like a problem but might indeed be a dilemma they should slow down, take a breath and notice their emotional response to what is in front of them.”

With increased clarity on the issue (the values in tension and how it is affecting them personally), leaders are ready to move to the external, to share their perspective with others. These might be the people involved in the issue (teachers, parents, lay leaders) or others who have a stake in it. The initial presentation to others is key. The natural proclivity is to say, “Yes, but….” Leaders proficient in managing dilemmas emphasize the need to use “Yes and…” language, moving from an adversarial to an inclusive stance, recognizing the importance and validity of both values. In doing this, leaders are modeling another piece of advice for interacting with colleagues and lay leaders which is to teach others the language and lens of enduring dilemmas. The educational leaders with experience using the lens of enduring dilemmas noticed that the more they taught others this practice the more the institution adopted it as a way of doing business. As one leader shared with us, “Everyone began to say, ‘We’ve got this challenge in front of us. Instead of reacting, let’s take some time to reflect on the values that are in tension. Then let's see what alternative strategies we can develop to manage the dilemma.’” (See Figure 3: Advice from Professionals in Their Own Words)

Figure 3: Advice from Professionals in Their Own Words

Movement from internal responses towards engaged external responses to enduring dilemmas is not linear. At any given point in the process leaders may need to go back and take note of their personal response to a particular interaction and to revisit the question, “What is really going on here?” This movement back and forth between internal and external is the result of the leader’s self-awareness and ability to read others’ responses.

Now more than ever, leaders face unprecedented issues and situations, sometimes on a daily or weekly basis. They need to care for their communities and reduce the anxiety engendered by a particular issue. The more they develop their ability to take a breath, step back and define with greater clarity the value tensions with which they and their institutions are grappling, the more they will understand that any solutions to the current situation are only for now and not forever. This will enable them, in the words of educational leader Lisa Langer, to “live with ambiguity and lead with clarity.”

References

Hill, L.A. and K. and Lineback. Being the Boss: The 3 Imperatives for Becoming a Great Leader. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2019.

Kidder, R. How good people make tough choices: Resolving the Dilemmas of Ethical Living. New York: Harper, 2009.

Lambert, M. “How do teachers manage to teach? Perspectives on problems in practice” in Harvard Educational Review. 55:178-194, 1985.

Turknett, R.L. and C.N. Turknett. Decent People, Decent Company: How to Lead with Character at Work and in Life. Mountain View, CA: Davies-Black, 2005.

[1] The research reported in this paper was supported by a generous grant from CASJE (The Consortium for Applied Studies in Jewish Education).

[2] We first learned about value tensions from Professor Debby Kerdeman of the University of Washington. She introduced us to important literature about value tensions including Kidder and Maggie Lambert’s seminal article in the Harvard Educational Review, “How do teachers manage to teach? Perspectives on problems in practice” (1985), a study of managing the dilemma of gender equity and classroom order in a math class.