Shir Hadash shel Yom: A COVID Journal in Hebrew Poems

In March of 2019 my beloved father was hit by a truck and killed, as he was making his way into a coffee shop to meet a friend. At the end of January 2020, my mother died, too. I had been saying Kaddish for a full year, first for my Dad, then for my Mom, when the novel coronavirus engulfed New York and the world, subsuming my personal grief in a larger, worldwide drama. My Kaddish practice thus became a daily record of the before and the during of COVID-19. God willing, it will become a record of how we got past it, too.

Saying Kaddish for a parent in the context of a traditional minyan is an exercise in hyper-repetition. Five kaddishes (two deRabbanan, three mourner’s) at every Shaḥarit service; three more (one deRabbanan, and two mourner’s) at Mincha/Ma’ariv, with an extra mourner’s kaddish thrown in after the supplemental Psalm (Psalm 27, To David the Eternal is my Light) for the month of Elul. Early in my Kaddish recitation, well before COVID-19, I knew that I was going to have add in some variation to sustain me through the days of repetitive chanting. And so it was that early on, I adopted a spiritual/pedagogical discipline, each week translating a different prayer-related Hebrew poem and offering commentary on it in the form of a weekly d’var Torah. I dubbed this practice “Shir Ḥadash shel Yom,” and it has persisted longer than I initially expected, as my Mom passed away a week before the conclusion of Kaddish for my father. I’ve likened that one week of overlap to the baton pass in a relay race—I was a sprinter on my high school track team—but instead of a sprint, this has been a marathon, one with unexpected turns along the way.

“And so it was that early on, I adopted a spiritual/pedagogical discipline, each week translating a different prayer-related Hebrew poem and offering commentary on it in the form of a weekly d’var Torah.”

The poem I chose for the morning of March 13, 2020, a year and a day after my father’s death, was “Hakhinisi” (Take me Under Your Wing), a 1905 poem by Ḥayyim Naḥman Bialik (1873-1934).

Take me under your wing,

Be for me mother and sister.

Your bosom will be a haven for my mind,

A nest for my far-flung prayers.

And at the merciful twilight hour,

Bend and I’ll tell you my secret suffering.

They say there’s youth in the world.

Where is my youth?

And I’ll confess another secret to you:

My soul has been seared by a flame.

They say there is love in the world.

What is love?

The stars deceived me.

There was a dream; it too has passed.

Now I have nothing at all in the world,

Nothing at all.

Take me under your wing,

Be for me mother and a sister.

Your bosom will be a haven for my head

A nest for my far-flung prayers.[1]

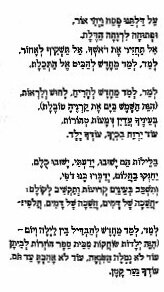

הַכְנִיסִינִי תַּחַת כְּנָפֵךְ,

וַהֲיִי לִי אֵם וְאָחוֹת,

וִיהִי חֵיקֵךְ מִקְלַט רֹאשִׁי,

קַן-תְּפִלּוֹתַי הַנִּדָּחוֹת.

וּבְעֵת רַחֲמִים, בֵּין-הַשְּׁמָשׁוֹת,

:שְׁחִי וַאֲגַל לָךְ סוֹד יִסּוּרָי

אוֹמְרִים, יֵשׁ בָּעוֹלָם נְעוּרִים –

?הֵיכָן נְעוּרָי

:וְעוֹד רָז אֶחָד לָךְ אֶתְוַדֶּה

;נַפְשִׁי נִשְׂרְפָה בְלַהֲבָהּ

אוֹמְרִים, אַהֲבָה יֵשׁ בָּעוֹלָם –

?מַה-זֹּאת אַהֲבָה

,הַכּוֹכָבִים רִמּוּ אוֹתִי

;הָיָה חֲלוֹם – אַךְ גַּם הוּא עָבָר

- עַתָּה אֵין לִי כְלוּם בָּעוֹלָם

.אֵין לִי דָבָר

,הַכְנִיסִינִי תַּחַת כְּנָפֵךְ

,וַהֲיִי לִי אֵם וְאָחוֹת

,וִיהִי חֵיקֵךְ מִקְלַט רֹאשִׁי

.קַן-תְּפִלּוֹתַי הַנִּדָּחוֹת

.י“ב אדר, תרס”ה

Bialik wrote this poem when he was 32 years old, in the aftermath of the horrific Kishinev pogrom, which he documented most memorably in his epic poem “B’ir Hahareigah.” It was in Kishinev that he met artist/writer Ira Jan (the pseudonym of Esphir Yoselevitch), with whom he came to have long-standing love affair.

In March 2020, the desire for familial and emotional shelter represented in “Hakhnisini” seemed extremely fitting for what I had already been going through in terms of familial loss, and what was beginning to feel like a world-wide retreat inside in the face of unprecedented pandemic. In the poem, Bialik’s speaker asks to be taken in under the sheltering wing of a “Shekhinah.” He imagines this Presence as a refuge for his abandoned prayers. He laments his departed youth; already then, this line brought to mind the vulnerability of older people to this deadly virus.

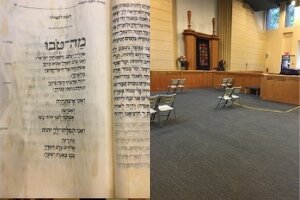

Little did I know that, immediately after presenting the poem, our rabbi would announce that that our synagogue, known affectionately as the Bayit (Home) would be closing indefinitely—and that this would be last morning minyan when I would be saying Kaddish or presenting a poem in person for the foreseeable future. Our own קן-תפילות (nest of prayers) was being emptied and abandoned, an unimaginable departure, given the more-than-a year’s worth of consecutive days that I had attended minyan in that space. Later that week, the Zoom tefilot began, a practice that soon became second nature. My “Shir Ḥadash shel Yom” regimen continued, too, but now, instead of handouts, there was Screen Share. I wrote follow-up emails with notes. The weeks began to blur into one another, and before I knew it, we were nearing Pesach.

The poem I alighted upon to teach as the “Shir Ḥadash shel Yom” as Pesach approached was “Al dalteinu Pasaḥ” (He Passed Over Our Door) by Leah Goldberg[2] (1911-1970), a poet who belonged to the generation of Hebrew poets that followed Bialik. “Al dalteinu Pasaḥ” considers, among other things, how the past can serve as a useful template for a post-traumatic present:

He passed over our door and there was light,

And the door was open wide.

Don’t look back, don’t glance behind,

Learn, learn anew to see the blue outside.[3]

Learn, learn anew to smell, to feel, to peer,

(Behold the sun is dipping her rays in the deep),

In your eyes, even now, are untainted tears,

So long as you’re young, you’ll easily weep.[4]

At night they’ll return, I know, return one and all,

They’ll suffocate in the dream, they’ll vilify,

You’ll lie down wide-eyed, and listen to their call:

“Blood darkness, blood darkness, pass by!”

(Behold laughing girls are returning home from school)

Learn, learn anew to distinguish night and day—

Hatred hasn’t been weaned[5], you haven’t loved your full,

You’re still a child at play.

“Al dalteinu pasaḥ” imagines a latter day “Passover,” an unidentified “He” having passed over the speaker’s home. Goldberg’s Lithuanian background, her years studying at the Universities of Berlin and Bonn during the rise of National Socialism, and her immigration to Palestine in the nick of time, in 1935, provide historical context for understanding this image, the threat of extermination having literally passed by Goldberg’s familial door. The poem thus engages the question of how one copes with fear and survivor guilt. Read today, it can be seen addressing the question of how one embraces the present and the future with COVID-19. Given the suffering and deaths of so many in the U.S. and in the world, how do we cope with the pressures and fears and persevere?

על דלתינו פסח ויהי אור-- In the first stanza, the poetic speaker, knowing that she and those in her house have been spared, and that her world has been created as if anew, coaches herself to keep her eye on the future – the blue (tkhelet) skies ahead. The words “ויהי אור” conjure up the earliest moments of the Creation story in Genesis 1, suggesting that an entirely new day has dawned, while the admonition not to look back recalls the instructions to Lot and his clan in Genesis 19 not to fixate on the carnage in Sodom as they flee for their lives. These two references indicate the need to press on forward at all costs, even with the knowledge, or especially with the knowledge of chaos and suffering.

In Numbers 15, however, one is enjoined to look at a “פתיל תכלת” in order to be reminded of God, Egypt, and the commandments. The reference to תכלת thus undermines straightaway the speaker’s determination not to consider the past. The same might be said of the ויהי אור reference, given that the book of Exodus recapitulates many aspects of the Genesis narrative.[6] In the Bible, the present moment is often processed in terms of intra-textual references to other biblical texts. Likewise, the repetition of “lemad, lemad,” reminds the reader, conversant in the language of the Haggadah, of the command issued by the Haggadah authors—“צא ולמד מה ביקש לבן הארמי לעשות” (Go and learn what Laban the Aramean sought to do). We come from a tradition that teaches us by way of engaging with rather than escaping from the past.

In the second stanza, the poetic speaker’s “here and now” approach is re-asserted. Lemad lemad,” she once again commands. Learn to use your senses again. Appreciate the physical world around you. Continue on with life despite ongoing, residual trauma. The speaker needs repeatedly to reconstitute herself, to start over, as if like a child, learning anew what it means to cry, to feel something in a pure unjaded way.

As the third stanza shows, the speaker remains haunted by ghosts of the past. At night everything comes back to her in full color: images of people being suffocated—victims of Hitler’s gas chambers?—figures who berate and accuse her, perhaps for having survived while they did not. Night descends upon the speaker as a חשכה של דמים, a bloody darkness, an image that at once evokes the חתן דמים episode in Exodus 4:24-26, the biblical plagues of blood and darkness, and more recent guilt-filled nightmares of death, all of which the speaker prays will pass over from her mind, like the Passover Angel of Death.

In the fourth stanza, the process of re-education resumes, as the speaker endeavors “להבדיל בין לילה ויום”—to separate (bloody dark) night from day. The word order in the traditional “Havdalah” blessing is “המבדיל בין יום ובין לילה.” The re-ordering here indicates that, for the speaker, night weighs more heavily on her mind than day. The laughing girls returning home from school come in to counter that nightmarish weight.

Taking a stand against darkness requires an acknowledgement that this work is ongoing. There is hatred (born of past suffering) that has not yet gotten its payback and/or from which the speaker has not yet been weaned. And yet, there is love yet to be fully given, too. The speaker is caught in the in-between, suspended between a traumatic past and a more optimistic present that she does not yet inhabit.

The parallels between this poem and our condition before Passover seemed obvious. We too were (and still are) in a liminal space with respect to the health aggressor that ravaged our communities and our world. If still healthy in our homes, then we were like those Israelites whose bloody doorposts had protected them from the worst of the plagues. In being passed over while others were suffering alone in hospital or placing themselves in harm’s way to help and heal, I could not help but feel gratitude for being alive, along with guilt that others around me, for no good theological reason, were taking sick. The protests against systemic racism in the U.S. that erupted later in the Spring made the poem’s observations about “unweaned hatred” additionally relevant and resonant.

And so it went. Months and several weeks of “Shirim Hadashim shel Yom” passed and our synagogue remained closed. On June 8, New York began its phased re-opening, and with it, our minyan began the slow, gingerly process of reconvening outdoors, on the patio of the synagogue, with mandatory sign-up in advance and limited attendance to prevent the spread of infection. Soon the strangeness of praying outside, chairs set up 12 feet apart as an extra precaution, with Zoom dial-ins to provide amplification and to counter to the sound of the cars on the Henry Hudson Parkway, became the new normal.

Four weeks later, on the week of the Fast Day of the 17th Day of Tammuz, which marks the beginning of the breach of the walls of Jerusalem, leading to the Destruction of the Second Jerusalem Temple, we were still on the patio, but plans were in place for minyanim indoors, in the event of rain. That week, I presented “Vehashirim hem avak ʿatikot,” (And Songs/Poems are the Dust of Antiquities, 1951 by Avraham Halfi (1906-1980), a member of the same Moderna circle of Hebrew poets as Leah Goldberg, a text which brought together the past, present and the the Jewish calendar, too, in an almost uncanny way.

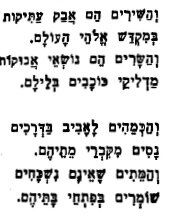

And songs are dust of antiquities

In the Temple of God of the World.

And the singers are the torch bearers

Lighting up stars in their nights.

And those who long on the byways for Spring

Flee from the graves of their dead.

And the dead who are not forgotten

Guard the doorways of their homes.[7]

Note the vav hahibbur, the word “and” in English, at the opening and throughout the poem, embedding it in an ongoing conversation or tradition about the definition and purpose of poetry and song.

And the the poem’s central image: as if anticipating the current medical/biological description of talking and singing as an activity that emits tiny aerosol particles that can potentially transmit virus, Halfi defines a poem or song as avak – tiny dust particles. But not just any dust: avak ʿatikot: hints or traces of the ancient past. And not just any ancient past, but the past of the mikdash (the Temple or Sanctuary). Writing in the context of a tradition of Hebrew poetry that includes poems of celebration as well as responses to calamity, Halfi reminds us that while actual physical Temples were destroyed, the purported psalms or songs of the Temples lived on. In each individual mikdash me’at—we keep the Temple service alive, as it were, through prayers that replace the sacrifices, and poems/songs that recall the Temple in its prior glory.

Notably, Halfi’s definition of (Hebrew) poetry is not limited to liturgy or to the kind of material that would be recited in the Jerusalem Temple. Instead he refers to poems/songs as the dust or residue of mikdash Elohei ha’olam, a universal, world-wide sanctuary to which all yearning, singing, poetic souls have access. As such Halfi calls attention to Hebrew poetry as world poetry, of lasting universal impact. To write a poem or sing a song in Hebrew is thus to take the ancient letters—the dust of antiquity—and make something new, bringing that past into the future and to many places in the world. Halfi models this recycling of the dust or letters of the past in the third line of the poem where he takes the word “avak” (dust) and turns it (through wordplay) into avukot – torches. According to the beautiful image, the singers or the poets are the torchbearers of the past; and with these torches, they light up the stars in their otherwise dark world.

The 1951 publication date of this poem sheds light, as it were, on the meaning of nighttime, not just as a time of day but as a tragic period, from which Israel and the world were only beginning to awaken. The second stanza refers to those yearning for Spring. In 1951, the State of Israel was quite literally in the first flowerings of its political Spring. In the immediate, dark, wintery past, were the devastations of the World War II and the 1948 War. There was great yearning in this springtime of the State of Israel to look away and flee from the carnage and victimization of the past. But in the same way that Hebrew letters and poems preserve the dust of antiquity and keep ancient times alive, so too the dead cannot and will not be forgotten. They linger at our doors, serving a guardian function and maintaining the residue of the past so as to inform the present.

“But in the same way that Hebrew letters and poems preserve the dust of antiquity and keep ancient times alive, so too the dead cannot and will not be forgotten. They linger at our doors, serving a guardian function and maintaining the residue of the past so as to inform the present.”

What this modern poem teaches in the present COVID-19 context is the enduring power of ancient words and carrying them on, if need be in revised form. Even though the tefilah in our synagogues is so different from the way it was a few months ago, the fact that we have been showing up and assembling safely and carefully, is helping to reconstitute not just our mikdash me’at but the mikdash Elohei Ha’olam – the larger sanctuary that is God’s world. That we are getting together not to sing at the top of our lungs without masks and super-spread coronavirus, but to say the words of our siddur quietly, with the help of Zoom amplification, is not just expedient but is a kiddush Hashem –a way of bearing the torch of civic responsibility, in the hope that we can eventually beat this virus.

For those of us who have been saying Kaddish these few or these many months and are looking toward saying Yizkor for our departed loved ones in the coming High Holidays, the final lines of the poem, which refer to the role of the dead as guardians of our homes are especially resonant, as they are the primary reason we are there. Kaddish is the ultimate avak ha’atikot: an ancient poem, replete with rhythm and rhymes, and rife with yearning for the full acknowledgement and reverence of God’s name. Kaddish imagines the best possible world, and saying it together is one important way of lighting up the stars in the dark night of familial and communal loss.

“Kaddish is the ultimate avak ha’atikot: an ancient poem, replete with rhythm and rhymes, and rife with yearning for the full acknowledgement and reverence of God’s name. Kaddish imagines the best possible world, and saying it together is one important way of lighting up the stars in the dark night of familial and communal loss.”

I delivered my thoughts on Halfi’s poem on Tuesday July 7; the fast of the 17th of Tammuz was on Thursday, July 9. The next morning, Friday July 10, just as services were underway, the skies opened up and began to rain down on those of us assembled on the patio. It was exactly four months and a week after the synagogue had closed down indefinitely, and there we were again, scrambling inside with our damp siddurim—mine opened to Ma Tovu— to continue praying indoors.

We had come full circle to Bialik’s “Hakhnisini”; we had returned to our abandoned nest of prayers. But this was an anxious homecoming, at best. Usually, as our rabbi noted, outside is a place of danger, and inside, the site of shelter and protection. COVID-19 had turned everything inside out, making the whole idea of refuge or shelter an uncertain concept. Exactly what our “ken tefillot” will look like in the coming months and year, with the High Holidays in the not-so-distant offing, remains to be seen. But I will be there, in whatever form, trying my best to leaven the old prayers with the newer insights of modern Hebrew poetry.

[1] A good deal of Bialik’s poetry can be found on the website of Project Ben Yehuda. https://benyehuda.org/read/5987

For Arik Einstein’s famous setting of the poem see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KmZ2H11cBu0

[2] Leah Goldberg, Shirim 2 (Tel Aviv: Sifriyat Po’alim, 1973), p. 226.

[3] Implication, the pale blue of the heavens. Also evokes the tkhelet of tsitsit. See Numbers 15: 38:

דַּבֵּר אֶל בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל וְאָמַרְתָּ אֲלֵהֶם וְעָשׂוּ לָהֶם צִיצִת עַל כַּנְפֵי בִגְדֵיהֶם לְדֹרֹתָם וְנָתְנוּ עַל צִיצִת הַכָּנָף פְּתִיל תְּכֵלֶת.

[4] Note the usage of the same verb in the second line of the poem, where the door is open wide, “lirvahah.” This line is hard to translate, because the phrase “עוד ירוח בכיך” can mean two opposite things: 1) your weeping will ease 2) your weeping will become more common or widespread. Given that, does the line mean that you’re a child now, and thus, your weeping pains you greatly. But soon enough, you’ll get used to it, and thus, your crying will ease? Or, that you’re still a child, having shed only a few, pure tears. But soon enough, with maturation, you’ll see how much pain there is in this world, and your weeping will become commonplace?

[5] This too is a tricky line, as the word גמל can mean either recompense (I.e., your hatred has been paid back) or wean.

[6] One good example of this is the use of the word teivah (ark) for the reed basket that baby Moses is placed in in Exodus 2. Ilana Pardes also sees a re-evocation of the berit ben habetarim in Genesis 15 in the parting of the Reed Sea. For more on the parallels between these biblical books see Ilana Pardes, The Biography of Ancient Israel (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000).

[7] Avraham Halfi “And Songs are Dust of Antiquities” from שירי האני העני (1951)